Chapter 14 Renaissance Europe, 1400-1500 - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

Title:

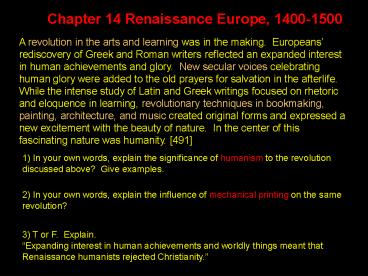

Chapter 14 Renaissance Europe, 1400-1500

Description:

Chapter 14 Renaissance Europe, 1400-1500 A revolution in the arts and learning was in the making. Europeans rediscovery of Greek and Roman writers reflected an ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:77

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: Chapter 14 Renaissance Europe, 1400-1500

1

Chapter 14 Renaissance Europe, 1400-1500

A revolution in the arts and learning was in the

making. Europeans rediscovery of Greek and

Roman writers reflected an expanded interest in

human achievements and glory. New secular voices

celebrating human glory were added to the old

prayers for salvation in the afterlife. While

the intense study of Latin and Greek writings

focused on rhetoric and eloquence in learning,

revolutionary techniques in bookmaking, painting,

architecture, and music created original forms

and expressed a new excitement with the beauty of

nature. In the center of this fascinating nature

was humanity. 491

1) In your own words, explain the significance of

humanism to the revolution discussed above? Give

examples.

2) In your own words, explain the influence of

mechanical printing on the same revolution?

3) T or F. Explain. Expanding interest in human

achievements and worldly things meant that

Renaissance humanists rejected Christianity.

2

Primary Source 1

Meat and eggs began to run out, capons and fowl

could hardly be found, animals died of pest,

swine could not be fed because of the excessive

price of fodder. A quarter of wheat or beans or

peas sold for twenty shillings, barley for a

mark, oats for ten shillings. A quarter of salt

was commonly sold for thirty-five shillings,

which in former times was unheard of . . . The

dearth began in the month of May and lasted until

the nativity of the Virgin September 8. The

summer rains were so heavy that grain could not

ripen. It could hardly be gathered and used to

make bread down to the said feast day unless it

was first put in vessels to dry. Around the end

of autumn the dearth was mitigated in part, but

toward Christmas it became as bad as before.

Bread did not have its usual nourishing power and

strength because the grain was not nourished by

the warmth of the summer sunshine . . . There can

be no doubt that the poor wasted away when even

the rich were constantly hungry . . . The usual

kinds of meat, suitable for eating, were too

scarce horse meat was precious plump dogs were

stolen. And according to many reports, men and

women in many places secretly ate their own

children.

SOURCE Johannes de Trokelowe, English chronicle

of Great Famine (1315)

3

Primary Source 2

I am a chieftain of war, and whenever I meet your

followers in France, I will drive them out if

they will not obey, I will put them all to death.

I am sent here in Gods name, the King of

Heaven, to drive you body for body out of all

France. If they obey, I will show them mercy.

Do not think otherwise you will not withhold the

kingdom of France from God, the King of Kings,

Blessed Marys Son. The King Charles, the true

inheritor, will possess it, for God wills it and

has revealed it to him through The Maid, and he

will enter Paris with a good company. If you do

not believe these tidings from God and The Maid,

wherever we find you we shall strike you and make

a greater tumult than France has seen in a

thousand years. Know well that the King of

Heaven will send a greater force to The Maid and

her good people than you in all your assaults can

overcome and by blows shall the favor of the God

of Heaven be seen . . .

Letter written on behalf of Joan of Arc to king

of England (1429)

4

Primary Source 3

There is not a limb nor a form, Which does not

smell of putrefaction. Before the soul is

outside, The heart which wants to burst the

body Raises and lifts the chest Which nearly

touches the backbone --The face is discolored and

pale, And the eyes veiled in the head. Speech

fails him, For the tongue cleaves to the

palate. The pulse trembles and he pants. The

bones are disjointed on all sides There is not a

tendon which does not stretch as to burst.

Georges Chastellain (ca. 1415-1475), Le Pas de

Mort (The Dance of Death)

5

Primary Source 4

I used to marvel and at the same time to grieve

that so many excellent and superior arts and

sciences from our most vigorous antique past

could seem lacking and almost wholly lost. We

know from remaining works and through references

to them that they were once widespread.

Painters, sculptors, architects, musicians,

geometricians, rhetoricians, seers and similar

noble and amazing intellects are very rarely

found today and there are few to praise them.

Thus I believed, as many said, that Nature, the

mistress of things, had grown old and tired. She

no longer produced either geniuses or giants

which in her more youthful and more glorious days

she had produced so marvelously and abundantly.

Leon Battista Alberti, On Painting (1434)

6

Primary Source 5

But whoever is born in Italy and Greece . . . Has

good reason to find fault with his own and to

praise the olden times for in their past there

are many things worthy of the highest admiration

whilst the present has nothing that compensates

for all the extreme misery, infamy, and

degradation of a period where there is neither

observance of religion, law, or military

discipline, and which is stained by every species

of the lowest brutality . . . I know not then,

whether I deserve to be classed with those who

deceive themselves, if in these Discourses I

shall praise too much the times of ancient Rome

and censure those of our own day. And truly if

the virtues that ruled then and the vices that

prevail now were not as clear as the sun, I

should be more reticent in my expressions, lest I

should fall into the very error for which I

reproach others. But the matter being so

manifest that everybody sees it, I shall boldly

and openly say what I think of former times and

of the present, so as to excite in the minds of

the young men who read my writings the desire to

avoid the evils of the latter, and prepare

themselves to imitate the virtues of the former

. . .

Niccolo Machiavelli (1469-1527), The Discourses