Topic 4b - An Overview of Prolog PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 142

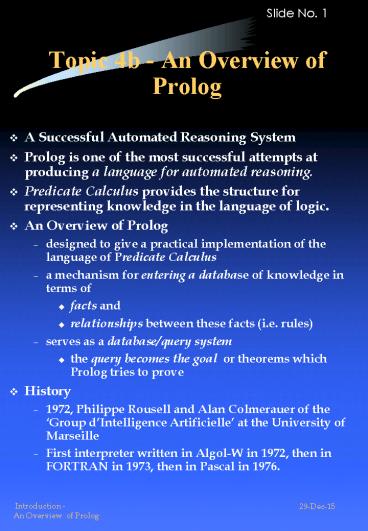

Title: Topic 4b - An Overview of Prolog

1

Topic 4b - An Overview of Prolog

- A Successful Automated Reasoning System

- Prolog is one of the most successful attempts at

producing a language for automated reasoning. - Predicate Calculus provides the structure for

representing knowledge in the language of logic. - An Overview of Prolog

- designed to give a practical implementation of

the language of Predicate Calculus - a mechanism for entering a database of knowledge

in terms of - facts and

- relationships between these facts (i.e. rules)

- serves as a database/query system

- the query becomes the goal or theorems which

Prolog tries to prove - History

- 1972, Philippe Rousell and Alan Colmerauer of the

Group dIntelligence Artificielle at the

University of Marseille - First interpreter written in Algol-W in 1972,

then in FORTRAN in 1973, then in Pascal in 1976.

2

Prolog References

- Prolog Programming for Artificial Intelligence

- Ivan Bratko

- 1986, Addison-Wesley

- Luger Chapters 6 , 13

- Programming in Prolog

- W.F. Clocksin and C.S. Mellish

- 1987, Springer-Verlag

- A Prolog Primer

- Jean B. Rogers

- 1986, Addison-Wesley

- The Art of Prolog

- Sterling and Shapiro

- 1986, MIT Press

3

Some Features of Prolog

- resolution theorem-proving (or unification)

- rewrites and stores database in the form of Horn

Clauses (See next slide - Omit at KG) - depth-first strategy in searching for a

pattern-match - is more declarative than procedural

- Is Prolog a True Logic Programming Language? No!

- A language must have extra features to those of a

purely logical nature - a stack scheduling policy

- communication predicates (I/O)

- control features (cut, repeat, ...)

- dynamic database modification (assert,

retract,....) - However, Prolog is still very close to a pure

logic programming language.

4

Horn Clauses (Omit at KG)

- Logic programming is commonly done using

predicate calculus expressions called "Horn

clauses" (named after Alfred Horn, who first

studied them). - Horn clauses are clauses that satisfy a

particular restriction - at most one of the literals in the clause is

unnegated. - Thus, the following are Horn clauses (assuming

that P, Q, Pi, P2,..., Pk represent propositions

each consisting of a predicate and the required

number of terms) - not PÚ Q

- not P1 Ú not P2 Ú ... Ú not Pk V Q

- not P1 Ú not P2 Ú ... Ú not Pk

- P

- These can be rewritten

- P gt QP1 Ù P2 Ù ... Ù Pk gt Q

- P1 Ù P2 Ù ... Ù Pk gt F

- P

- The third of these expressions employs F to

indicate falseness or the null clause.

5

Horn Clauses - Contd.(Omit at KG)

- These are often written in a "goal-oriented"

format in which the implied literal (the goal) is

on the left and ',' is used for the AND operator - Q lt P

- Q lt P1, P2, , Pk

- lt P1, P2, , Pk

- P lt

- The third and fourth examples above show cases in

which the goal arrow has nothing to its left (in

the former case) and nothing to its right (in the

latter case). - The null clause is a Horn clause, and can be

written lt - Horn clauses in the goal-oriented format are used

to program in Prolog.

6

Useful in Solving the Problem of Non-monotonic

Reasoning

- In monotonic logic, the axioms are invariant,

even though new information may indicate that

certain axioms must be false. - Non-monotonic reasoning provides for updating the

set of axioms to reflect the best available

information (using assert and retract).

7

- What topics are we covering?

- Introduction to Prolog

- Facts

- Queries

- Variables

- Rules

- Finding solutions

- What will we be able to do?

- understanding of fact database

- able to explain Prolog code

- able to trace evaluation of a goal

- able to define simple Prolog relations

8

How Does Prolog Relate to Other Languages?

- Wirth

- Programs algorithms data structures

- Kowalski

- Algorithms logic control

- i.e. what we are trying how we go about

- to achieve achieving it

- i.e. declarative V's procedural

- semantics semantics

9

Where to find Prolog at FIT

- SWI Prolog in FIT Labs

10

Using SWI-Prolog

- We will use a version of Prolog which runs under

Linux, Windows xx. You should visit the FITs

OLT or the following URL, download the

appropriate version and get it running on your

own PC. The ftp sites are indicated at this URL - http//www.swi.psy.uva.nl/usr/jan/SWI-Prolog.html

- use pfe or Notepad as default editor

- ignore comments in tutorials re

- -state(token...........

- This does not apply to SWI Prolog.

- Note the extensive manual available at the SWI

site

11

Using SWI Prolog (Contd)

- Editing or Creating a file from within SWI

Prolog - ?- edit(myprog).

- This edits myprog.pl and then automatically

reconsults the file. - To exit, use

- ?- halt.

- A consulting error gives an error message and

an error menu the meanings of which can be

easily discovered. - help

- ?- help. -gt a brief help

file - ?- help(get). -gt help on the

command get - Tracing

- trace. opens a trace window to enable

tracing of the evaluation of the goal (query) - notrace.

- Use 't' to turn on trace during SWI execution.

- Use 'c' to turn on creep.

12

Using SWI Prolog (Contd)

- When consulting files in subdirectories using SWI

Prolog, you need to take care using slashes. A

single forward slash or TWO back slashes will be

accepted. See examples below - 1 ?- 'a/a'.

- a/a compiled, 4.72 sec, 2,152 bytes

- Yes

- 2 ?- 'a\a'.

- WARNING No such file user a

- No

- 3 ?- 'a\\a'.

- a\a compiled, 4.72 sec, 2,152 bytes.

- Yes

13

Using SWI Prolog (Contd)

- SWI runs in a window that behaves a little

differently from other Windows applications. - In particular, you will need to capture output

into a file to print and submit for your

assignment. One way of doing this is a follows - You can drag the mouse over a SWI screen. Only

the first line is highlighted but in fact all

lines covered by the mouse are now able to be

copied. - Then type 'CTRL C'. Now open the window you wish

to copy to. Click the mouse to position the copy

position. Type 'CTRL V'. The text will appear

on one line as 'Enters' are translated to

graphics characters. Simple replacing of the

graphics characters by 'Enters' will create the

text properly. - You need to do this carefully to ensure that the

text is exactly what I will see when I run your

program from the disc you supply with your

assignment.

14

Using SWI Prolog (Contd)

- When you load Prolog code using the SWI compiler,

you may generally ignore any warnings that refer

to 'Singleton Variables'. - Most other compilers do not give this warning.

- If you wish you may get rid of this problem and

some others by putting the following at the

beginning of every SWI program - - style_check(-atom).

- - style_check(-singleton).

- - dynamic(asked/2).

15

Getting Started (SWI Prolog assumed)

- 1. (Rarely used) You may enter clauses

interactively from the keyboard - c user. i.e. read clauses from the

keyboard - is_integer (0).

- etc. a set of

Prolog clauses (facts and rules) - etc.

- Z. to exit entry phase and return to

query mode. - 2. (Commonly used) You may use any DOS editor

(such as Notepad, pfe, etc) to form a file of

Prolog clauses ( pro1.pl in SWI Prolog). - 3. To consult this file from within Prolog, use

- pro1.pl. This is a shorthand version

of consult('pro1.pl').

16

- In most versions of Prolog, you may omit the s

if the filename does not contain an extension.

This then becomes pro1. This is also a

shorthand notation for the full form

consult(pro1). - If you need to edit this file and wish the new

definitions of clauses to overwrite the old ones,

you need to use - reconsult(pro).

- Summary of 4 ways of consulting Prolog clauses

into the database - 1. user. i.e. consult clauses directly

from the keyboard or - 2. pro1. 3

ways of consulting from a file. - 3. consult(pro1). or

- 4. consult(pro1.xxx).

17

Reading programs consult, reconsult

- We can communicate our programs to the Prolog

system by means of two built-in predicates - consult and

- reconsult.

- We tell Prolog to read a program from a file F

with the goal - ?- consult( F).

- The effect will be that all clauses in F are read

and will be used by Prolog when answering further

questions from the user. - If another file is consulted at some later time

during the same session, clauses from this new

file are simply added at the end of the current

set of clauses. - X is a special notation for consult(X).

- file1, file2, file3 is also possible.

- The built-in predicate reconsult is similar to

consult. A goal - ?- reconsult( F).

- will have the same effect as consult( F) with

one exception - If there are clauses in F about a relation that

has been previously defined, the old definition

will be superseded by the new clauses about this

relation in F. - The difference between consult and reconsult is

that - consult always adds new clauses while

- reconsult redefines previously defined relations.

reconsult( F) will, however, not affect any

relation about which there is no clause in F.

18

Aspects of Declarative Languages

- Control separate

- the Prolog system does the matching,

backtracking, etc - Control can be upgraded (e.g. parallelism)

without affecting the source code. - Control can extract information in a variety of

ways (i.e. not limited to the outcome of one

particular procedure) (e.g. append, etc.) - less to write since no need to worry about

control.

19

Prolog

- A goal-directed language - Note

- A logic programming language

- i.e. all predicates are evaluated to True or

False - A declarative language

- i.e. you say what you want (see next slide for

more details) - A relational language

- A symbolic language (Therefore useful for AI

applications) - i.e. suitable for manipulating symbols, cf Lisp

- A Fourth/(Fifth) generation language

- A query-based (conversational) language

- A simple syntax

- A dynamic environment

- assert new facts and rules

- retract new facts and rules

- Solutions found (almost) automatically

- (i.e. the how is done for you)

20

Applications of Prolog

- (Mostly in the area of Artificial Intelligence)

- Expert Systems (and shells)

- Natural Language Understanding

- Language Translation

- Symbolic manipulation systems (e.g. equation

- solvers, theorem provers, program derivation)

- Prototyping Databases in Prolog

- Dynamic relational databases

- Control and monitoring of industrial processes

- VLSI CAD Tools (e.g. editor - implementation is

order of magnitude smaller than in imperative

languages such as C) - Analysis of VLSI designs at register transfer

level - (hardware design tool)

21

Applications of Prolog (Contd)

- Portable Parallelising Pascal Compiler

- Natural Language Explanations from Plans

- Machine learning

- Stream Data Analysis (e.g. of stock market

reports) - "Assembly language" for Fifth Generation Language

22

Prolog Overview

- Prolog Programming features

- 1. declaration of some FACTS about objects and

their relationships - 2. declaration of some RULES about objects and

their relationships - Note at this stage programming stops and

querying starts - and

- 3. asking QUESTIONS about objects and their

relationships. - As facts and rules are defined Prolog stores them

in a database. Then you can (conversationally)

ask Prolog questions about the knowledge in the

database. - data types are CONSTANTS, VARIABLES, or

STRUCTURES (see later) - 1 and 2 above constitute a Prolog Program

- 3 is the process of querying the Prolog system

once clauses have been consulted. - More Simply

- Prolog Programs statements about the world

- Prolog queries theorems we would like to

have proved - i.e. we tell the Prolog system what is true and

ask it to test hypotheses.

23

Defining FACTS - See Bratko Chapter 1.1

- Example of a Fact

- predicate arguments

-

a predication - likes( john, mary).

- relationship objects

- (Note relationships and constant objects

must begin with a lower case letter.) - Syntax

- - objects separated by commas ','

- - fact terminated by full-stop '.'

- - objects of relationships within parentheses

- '(...)'

24

FACTS - (Contd)

- Semantics (i.e. Meaning)

- We may decide that the fact has the semantics

- "John likes Mary" or indeed

- "Mary likes John",

- but we must decide on one and stick to it.

The names have no meaning to Prolog - they are

just symbols to be manipulated. - So make sure you explain via comments the

semantics of a relation at the start of its

definition!

25

FACTS - (Contd)

- constant constant

- female(jane). Jane is a

female. - structures

- father(john, mary). John

is Mary's -

father. - gives(john, book, mary).

-

John gives the -

book to Mary. - gives(john, has(cover, green))

- Be careful as to what objects the symbols

refer. - For example, gold -

- valuable(gold).

- This is a slightly different interpretation

of a fact. Is it a particular piece of gold or is

it the element? (or indeed the colour)? The

ambiguities must be resolved by the programmer's

mind and he should be consistent.

26

FACTS - (Contd)

- As the programmer's mind is volatile and

non-transparent it is a good idea for the

programmer to actually write down what

interpretation is placed upon the symbols and

relations.

27

A database Interpretation of Prolog

- predicate arguments record

- e.g. book(tanenbaum,a,computer_networks,

- prentice_hall,1981,.....).

- or more clearly

- book(

- tanenbaum,a,

- computer_networks,

- prentice_hall,

- 1981,

- .

- .

- ...

- ).

- A collection of facts is called a database in

Prolog.

28

QUESTIONS (or Queries or Goals)

- ?- owns (mary, book).

- Note that some versions of Prolog insist on a ?

to terminate a query. - One possible meaning Does Mary own a book?

- Prolog searches through the database looking

for a pattern match with - owns (mary, book)

- or something equivalent to it or that it can

infer is true. - Two facts match if the predicate and the

arguments are the same (as in e.g. above). When

a match is found in answer to a question, Prolog

answers "yes", otherwise "no". - "yes" means that it was provable by the facts

and rules in the database. - "no" means that it was NOT provable by the

facts. - Prolog knows nothing directly about the real

world - only about what is in its database.

29

- Database

- likes(joe, fish).

- likes(joe, mary).

- likes(mary, book).

- likes(john, book).

- Questions

- ?- likes(joe, money). gt no

- ?- likes(mary, joe). gt no

- ?- likes(mary, book). gt yes

- ?- likes(john, france). gt no

- ?- likes(fred, mary). gt no

- Constants

- We have been using constant objects

- e.g. joe, gold, mary, book, ...

- They remain completely unchanged through the

life of the database.

30

VARIABLES

- The questions

- Does John like books ?

- Does John like Mary ?

- are fairly restricted sorts of questions.

- A more interesting question is

- What does John like ?

- a variable

- Here we are asking for everything that John

likes. We will use a variable to represent

something that John likes. - Syntax of Variables

- Must start with a capital letter.

- Note the following

- Instantiated variables - variables with a

value assigned to them, i.e. we have a

particular instance of something that the

variable represents - Uninstantiated variables - variables with no

value known

31

- Variables have dynamic scope. This means that

they are given one value (when it is found) which

it keeps for the duration of that execution

within any 1 rule. Once a solution is found then

its value is reported and another solution is

searched for (if requested). This new search is

a new execution and the variable starts out with

no value (i.e. uninstantiated). If a search for

a solution fails then another search (and another

execution)will look for a valid value for the

variable. - Given these facts

- likes( john, flowers).

- likes( john, mary).

- likes( john, golf).

- likes( paul, mary).

- and the Goal

- ?- likes(john, X).

- which involves an uninstantiated variable - X,

the meaning is - set X to something John likes, i.e.

- instantiate X to something.

- Here, Prolog will return in order

- X flowers

- X mary

- ...

32

- i.e., make the question True by giving X a

suitable value. - ?- likes(john, X).

- X flowers

- X mary

- X golf (CR)

- No

- ?-

- ?- likes(X, mary).

- X john

- ...........

- X paul

- Think of Prolog as having a marker in the

database marking its current match(es).

33

Conjunction of Sub-Goals

- Goals may be compound goals consisting of a

number of sub-goals connected by , (the logical

AND). In this case, all of the sub- goals need

to succeed for the overall goal to succeed. - For example,

- ?- likes(john, mary), likes(mary, john).

- Syntax

- comma (,) means and (conjunction)

- Meaning gt

- Does John like Mary and Mary like John?

- i.e. Do John and Mary like each other ?

- ?- likes(mary, X), likes(john, X).

- Meaning gt

- Find something liked by both Mary and John.

- Prolog tries to match each goal in turn.

- Each goal has its place marker.

- Prolog attempts a complete match even if it

means - retrying the first goal until the database is

exhausted.

34

The AND Built-In Predicate ,

- Note that , is really a predicate.

- Internally, the implementation of

- likes(mary, X), likes(john, X).

INFIX Notation - is

- ,(likes(mary, X), likes(john, X)). PREFIX

Notation - In the first case, , is acting as an infix

operator. - In the second case, , is acting as a prefix

predicate - AND. - Other ,s are acting as argument separators.

- A Note on Operator Notations

- INFIX a b

- PREFIX -a

- POSTFIX a!

35

Finding Solutions for Conjoined Goals

- Database

- likes(mary, food).

- likes(mary, wine).

- likes(john, wine).

- likes(john, mary).

- Prolog processing for

- ?- likes(mary, X), likes(john, X).

- proceeds as follows

- - X uninstantiated, search starts for first

sub-goal - - Marker 1 is set and X is instantiated to food

everywhere in question (i.e. in both places) - - The the second sub-goal becomes likes(john,

food). This is sought and the search fails. - - backtrack to find another value of X which

may succeed. - - X becomes uninstantiated again and marker 1

proceeds from its current position seeking

another match for likes(mary, X)

36

- likes(mary, wine) is found, which satisfies the

first goal, so X instantiated to wine. - Marker 2 starts from the beginning and finds

- likes(john, wine).

- Since X instantiated to wine satisfies both goals

then the overall goal succeeds and X wine is

reported to the user. - Prolog then goes on to find any further solutions

(relational rather than functional).

37

Another Example of Compound Goals(For you to

read)

- Assume the database

- 1- eats(rhonda, apples).

- 2- eats(henry,honey).

- 3- eats(rhonda,icecream).

- 4- eats(peter,passion_fruit_parfaits).

- 5- eats(henry,icecream).

- 6- eats(peter,honey).

- ?- eats(henry,X),eats(rhonda,X).

- sub-goal a sub-goal b

- Goal Clause Result Instantiation/Action

- a 1 fail

- 2 success if X

honey,(a) marker at 2 - b 1..6 fail backtrack and

uninstantiate X, - b is now

eats(rhonda,honey) - a 3,4 fail

- 5 success if X

icecream, - (a)

marker at 5

38

The OR Predicate

- is the OR predicate,

- i.e. it gives the disjunction of 2 or more

sub-goals - e.g. likes(X,tennis)likes(X,golf).

- (B) (C)

- or

- Thus, the overall goal is true if (B) is true OR

(C) is true.

39

RULES

- Rules allow greater flexibility in declaring

knowledge. Whereas facts are true in all cases,

rules define "facts" that depend upon the truth

of other facts. That is, the head of a rule may

not always be true - it will depend upon whether

its subgoals succeed or not. - rule (Definition)

- A relationship between a "fact" and a list of

sub-goals which must be satisfied for that "fact"

to be true - a general statement about objects and their

relationships. - Syntax

- z - a, b, c, ..

- i.e. If a and b and c and , then z or

- a and b and c and z ('implies z')

- z (is true) if a and b and c and (are all

true) - ltconclusion or ltrequirements or

- consequence or - antecedents or

- headgt bodygt

- The conclusion of the rule will be true if the

requirements are satisfied. The head consists of

exactly one predicate, and the body consists of

one or more predicates joined with and (,) or

or ().

40

Undefined sub-goal predicates

- If SWI Prolog tries to satisfy a sub-goal

involving a predicate that does not exist in the

database - (either because it was never defined or

- because it was retracted during execution)

- then during execution SWI issues a 'Warning',

halts execution and goes into 'trace' mode. - Most other versions ignore this and fail.

- This in some programs using SWI, you need to

insert a dummy clause in case this happens.

41

- Example

- Suppose that John likes everybody. We could

say - likes(john, mary).

- likes(john, paul).

- But it would be better to try to say

- John likes any object if it is a person.

- In prolog, we do this via

- lokes(john, X) - person(X).

- Other examples of rules (in English)

- John buys wine if it is cheaper than beer.

- X is a bird if

- X is an animal, and

42

Translating English-like rules into Prolog

- John likes anyone who likes wine.

- John likes something if that something likes

wine. - John likes X if X likes wine.

- if

- In Prolog

- likes(john, X) - likes(X, wine).

- More examples

-

and - likes(john, X) - likes(X, wine),

- likes(X, food).

43

Rules Using the Disjunctive ''

- is the OR predicate, i.e. it gives the

disjunction of 2 or more sub-goals - e.g. likes(john,X) - likes(X,tennis)

likes(X,golf). - (A) (B)

(C) - if

or - Thus, (A) is true if (B) is true OR (C) is

true. - It is used less frequently than the , as two

rules with the same LHS achieve the same effect.

Thus, the above is equivalent to - likes(john,X) - likes(X, tennis).

- likes(john,X) - likes(X, golf).

- Another example

- likes(john, X) - female(X) likes(X, wine).

44

Finding Solutions for Goals Involving Rules but

with No Variables

- An example of simple backtracking.

- Suppose the database contains the following

- boy(john).

- boy(marmaduke).

- boy(bertram).

- boy(charles).

- girl(griselda).

- girl(ermintrude).

- girl(brunhilde).

- possible_pair(X,Y) - boy(X), girl(Y).

- And the query is

- ?-possible_pair(X,Y).

- The response would be

- Xjohn, Y griselda

- Xjohn, Y ermintrude

- Xjohn, Y brunhilde

- Xmamaduke, Y griselda

- Xmamaduke, Y ermintrude

- Xmamaduke, Y brunhilde

45

Backtracking with Sub-Goals in Rules Illustrated

- fred - a, b, c,

d, e, f, g.

The solution would be formed from instantiations

formed from the indicated successes.

46

Finding Solutions for Goals Involving Rules with

Variables

- Database

- Facts

- male(albert).

- male(edward).

- female(alice).

- female(victoria).

- parents(edward, victoria, albert).

- parents(alice, victoria, albert).

- Rule

- sister-of(X, Y) - female(X),

- parents(X, M, F),

- parents(Y, M, F),

- not (X Y).

- Or, using more meaningful names

- sister-of(Sister, Sibling) -

female(Sister), - parents(Sister, Mother, Father),

- parents(Sibling, Mother, Father),

- not(Sister, Sibling).

47

- Prolog processing for

- ?- sister-of(alice, edward).

- proceeds as follows

- Step 1 Rule sister-of located and X instantiated

to alice and Y set to edward from the goal. - Step 2 The first sub-goal, female(alice), is

found in the database of facts so succeeds. - Step 3 Search to match the second sub-goal,

parents(alice, M, F). This is found as a fact so

succeeds. Variable M is instantiated to

victoria, and variable F is instantiated to

albert. - Step 4 Prolog now tries to satisfy the third

sub- goal so searches for - parents(edward, victoria, albert)

- (as Y, M and F have all been instantiated).

This fact is found so the sub-goal succeeds.

48

- Since all sub-goals have now succeeded then

the overall goal, sister-of, succeeds (i.e. has

been determined to be true) - so Prolog answers

yes.

49

- Prolog processing for

- ?- sister-of( alice, X ).

- proceeds as follows

- Step 1 Rule sister-of located and X (of

sister-of rule) instantiated to alice and Y

(from the rule in the program) is set to variable

X from the goal. Note that X(goal) and Y

variables are both uninstantiated. - Step 2 The sub-goal, female(alice), succeeds

as before. - Step 3 Variable M is instantiated to victoria,

and variable F is instantiated to albert - as

before. - Step 4 Y is unknown, so search for

- parents(Y, victoria, albert)

- The fact parents(edward, victoria, albert)

matches this, so Y is instantiated with edward.

50

- Step 5 Since all sub-goals have now succeeded

then the overall goal, sister-of, succeeds with X

being instantiated to edward . - Prolog2 answers

- X edward.

- More(Y/N)? Y

- SWI achieves the same effect via

- X edward

- Now Prolog tries to find another solution to

sister- of. Steps proceed as from Step 4, with Y

uninstantiated again. This time through, Step 4

will match with parents(alice, victoria, albert),

so Y (and then X) will be instantiated to alice.

- Prolog answers

- X alice

51

Recursive Rule Definitions (or Recursive

Relations) - See Bratko Chapter 1.3

- You may be familiar with recursion from

experience with other languages. - A relation is expressed in terms of itself.

- For example, consider the definition of the

ancestor relation. - / A is the parent of B in parent(A,B)/

- / A is the ancestor of B /

- ancestor(A,B) - parent(A,B).

- ancestor(A,B) - parent(C,B),

ancestor(A,C).

52

Form/Dangers of a Recursive Procedures

- Forms

- Any recursive procedure must have-

- (i) a nonrecursive clause defining the base

case (such as the first rule of 'ancestor') - (ii) a recursive rule where the first subgoal

generates new argument values followed by

recursive subgoals using the new argument values

(such as the second rule of 'ancestor') - Dangers

- Take care to avoid endless loops during

recursion - Circular definitions

- parent(X,Y) - child (Y,X).

- child(A, B) - parent (B,A).

- Left Recursion

- i.e. when a rule causes the invocation of a goal

that is essentially equivalent to the original

goal - person(X) - person(Y), mother (X,Y).

- person(adam).

- ?- person(A).

53

The Meaning of Prolog Programs(Semantic Models

of Prolog)

- Declarative Model

- The meaning of a Prolog predicate is considered

as a definition of a static relation between

terms (the arguments). - Abstract Machine Model

- This is a behavioural view of the Prolog

interpreter evaluating Prolog language

constructs. - It is similar to the behavioural semantic models

of other programming languages - which at the

base level are imperative. - This model accounts for all extra-logical effects

(i.e. input/output and control side-effects). - It may be tracked via trace.

54

Towards a Formal Definition of Prolog - Data

Objects (and Prolog Syntax)

- Programs are built from terms.

- A term may be

- constant, or

- variable, or

- structure (see later)

- A term is written as a sequence of characters

- AB..Zab..z01..9

- -/\ltgt.?_at_

- Characters are treated as integers between 0 and

127, i.e. the decimal equivalent of the ASCII

code. - A constant is a name of

- an object or

- a relationship

- A constant may be

- an atom

- an integer

55

Prolog Syntax(Continued)

- An atom is formed by

- letters and digits

- begins with a lowercase letter and may use _

for readability - symbols

- e.g. , --gt

- A variable has a name beginning with

- (1) an uppercase letter, or

- (2) the character _

- e.g. _abc, _16

- _ by itself is called the anonymous variable

(see later)

56

Prolog - A Partial Syntax(Omit the next 3 slides

for ITB742 at KG)

- Program

- Clause

- Rule

- Fact

Clause

Rule

Fact

, or

.

Predication

-

Predication

.

Predication

57

Prolog - A Partial Syntax (cont)

,

- Predication

- Term

- Constant

- Atom (simple)

(

)

Predicate

Argument

constant

variable

structure

'

'

character

letter

lower case letter

digit

58

An example of a predication

- e.g. predication

- likes('Mike Jones', cars).

in Prolog

59

Data Objects in Prolog

- data objects

- simple objects

structures - constants variables

- atoms numbers

- (usually integers

- with most versions

- of Prolog)

60

Structures

- Structures (or Compound Objects - see

earlier) - Compound objects can be regarded and treated

as single objects. - A structure is a single object which consists of

a collection of other objects called components. - They allow a group of related information to be

treated as a single object. - Syntax

- ltfunctorgt ( ltcomponentsgt ... )

- where each component can itself be a

structure. - Components are separated by commas (,).

- ltfunctorgt is the name of the structure.

- Prolog programs are made of terms. Terms can

be constants, variables or structures. (cf.

Scheme) - Example

-

structure components - owns(john, book(wuthering-heights, author(emily,

bronte) ) ).

functor components

61

Structures (Contd)

- Creating and Accessing Components of General

Structures using a 'built-in' predicate (our

first) - functor(T,F,N) (a built-in predicate)

- "T is a structure with functor F and arity

(number of components) N." - If T is instantiated it must be an atom, i.e.

- an atom is a structure with arity 0

- ?- functor (likes (john, money), F, N).

- N 2,

- F likes.

- ?- functor(ab,F,N). ab

(a, b) internally - N 2,

- F

62

Recursive Data Structures

- The name of the structure is called the functor.

- The number of objects contained by the structure

is its arity. - Both functor name and arity must match for the

structures to be able to match. - The objects (or components) contained within a

structure can be any type of objects - simple

(e.g. numbers or symbols), complex (i.e. other

structures) and even recursive (objects of the

same structure).

63

- You dont need pointers to have a recursive data

structure! - For example (tree)

- left root

right - This is equivalent to the tree

- tree-4

- tree-3

tree-6 - tree-2 end tree-5

end - end end end

end

64

Anonymous Variables

- If you are not interested in the values of

particular arguments, then you can just "ignore"

them using anonymous variables. Anonymous

variables will match with anything, i.e. they act

as place holders. - NB Two or more uses of anonymous variables

in a clause do not instantiate to the same object

- i.e. each one is distinct and separate (even

though they are represented by the same sign). - For example,

- ?- owns(john, book( _ , author( _ , bronte) )

) - may mean

- Does John have any book by any of the Bronte

sisters?

65

Unification A Form of Pattern Matching

- The purpose of the Prolog unification process

is to - (i) decide which clause to invoke

- (ii) pass the actual parameters to the clause

- (iii) deliver the results

- Unification is a bi-directional process - i.e.

information can flow either way (i.e. either by

an input parameter or by an output parameter (but

not both!)) depending on usage. - e.g. If owns(a, b, X, P).

- is an item in the database,

- and it is unified with the query

- owns(A, B, tom, Q).

- then A is instantiated to a,

- B is instantiated to b,

- X is instantiated to tom, and

- P and Q share

- from this time onwards.

- See details following.

66

Unification Rules

- Unification (a special from of pattern

matching) obeys the following Rules - 1. A variable unifies with a constant or a

structure. - e.g. X joan gt X instantiated to joan

- 2. A variable unifies with a variable.

- e.g. X Y gt X and Y share the same

value. - 3. The anonymous variable (_) unifies with

anything. e.g. alice _ - 4. A constant unifies with a constant if they

are identical. - e.g. alice alice gt true

- 10 10 gt true

- 5. A structure unifies with a structure if the

structure names (or functors) are the same and if

the arguments can all be unified. - e.g. father(albert) father(X)

- gt X albert

67

- NB The structures typically have a number of

arguments and they must be unified in a "do-able"

order. - NB Pattern-matching for lists (e.g. HL) is

as described above after converting the list

notation to standard syntax (i.e. the dot "."

structure).

68

Evaluating a Prolog Query

- Evaluation can be understood as a recursive

cycle of unification (pattern matching) and

subgoal evaluation. - Evaluation is goal-directed.

- Evaluation is triggered by a query (initial

goal). - Evaluation descends as deep as necessary into

the structure of the program to find facts that

validate the query. - It returns having proved or failed to prove

the goal, with zero or more instantiations. - The search space for solutions consists of a

tree (with possibly infinitely long branches !).

Prolog searches this tree using a depth-first

strategy. - You can quickly see that Prolog may start

looking for a solution down an infinite-length

branch and never return - while the solution is

sitting in the next branch along. This is why

we must be careful with the order of our subgoals

in a rule.

69

- Prolog's search strategy is not perfect.

There may be solutions but Prolog may fail to

find them. - Prolog is limited. It is a restricted class

of logic programming in order to be executable. - Parallel implementations of Prolog may

provide a better implementation of logic

programming.

70

Steps of Evaluation

- 1. Find relevant Clause

- When a goal (query/question) is entered by

the user, the goal is activated. - The interpreter searches through the clauses

(facts and rules) for the first clause whose head

unifies with the query. - For the goal to unify with the head of a

clause, both must have the same predicate name

and same arity (number of arguments), and all

arguments of both must unify. - 2. Evaluate subgoals

- When a clause matches, it is activated and

each of the subgoals in the body of the clause is

evaluated in the same way as the original query

(i.e. recursively). - If the body is empty (i.e. a fact) then it

succeeds.

71

- 3. Backtrack

- If no clauses match then the interpreter

backtracks. - It returns to the last successful subgoal,

undoes any bindings (instantiations) , and begins

looking for any more matching clauses. (A place

marker is associated with each subgoal.) - 4. Report Result(s)

- On success, Prolog prints out the values of

any variables in the query or yes (true) if

there were no variables. - On failure, gt no

72

Declarative vs Procedural Meaning of Prolog

Programs

- Consider the Prolog rule

- P - Q, R.

- i.e. if (q and r) then p

- The Declarative Meaning

- P is true if Q is true and R is true.

- The Procedural Meaning

- To solve problem P, first solve the

sub-problem Q

and then solve

the sub-problem R. - or

- To satisfy P, first satisfy Q, and then satisfy

R.

73

The Meaning of Prolog Programs

- Procedural Model

- A Prolog program is executed (computed)

according to the following algorithm - 1. To execute a goal (original query or

sub-goal), match it against the head of a clause

(fact or rule) and then execute the sub-goals in

the body of the clause. - 2. If no match can be found - backtrack.

That is, go back to the most recently executed

goal and seek another solution for it. - 3. Execute goals in left-to-right order.

- 4. Try clauses in top-to-bottom order.

- Note that the control strategy is goal-driven

i.e. information is found in order to prove (or

deduce) the goal. - 1. To execute a goal (original query or

sub-goal), match it against the head of a clause

(fact or rule) and then execute the sub-goals in

the body of the clause. - 2. If no match can be found - backtrack.

That is, go back to the most recently executed

goal and seek another solution for it. - 3. Execute goals in left-to-right order.

- 4. Try clauses in top-to-bottom order.

- Note that the control strategy is goal-driven

i.e. information is found in order to prove (or

deduce) the goal.

74

Representation of Lists (Lists in Prolog)

- Definition A list is either

- an empty list or

- it is a structure that has two components

- the Head (the first element of the list) and

- the Tail (the list of remaining elements)

- Lists are structures using the dot "." functor

(cf 'cons' in Lisp for ITB442 students). - functor(a,b,c,F,N).

- N 2,

- F . (the functor for generating lists)

- This result comes from the internal

representation of the list above as .(a, b,

c). - .(H,T) is the base notation but it may also be

written as H.T (as . is also defined as an

operator) or HT. - This last form is the most common.

- In general a list is written as

- H T

- Note a, b, c is represented internally as

.(a, b,c) - It may also be referenced as a b.c using

the H T form.

75

, , , , Notation

- This important class of data structure is given

a convenient notation as shown below, but at the

base level is just a structure (a compound term). - Lists may also represented as a number of

comma-separated elements surrounded by square

brackets. - e.g. a, b, c

- This is written in standard syntax as

.(a,.(b,.(c,))) - You can also access the second and third

elements by splitting the tail- - Head1, Head2 Tail unified with a, b, c

gives - Head1 a, Head2 b, Tail c

- a,b,c,d ab,c,d)

- a,b c,d).

- a,b,c d).

- a,b,c .(a,b,c) a.b,c

- .(a,.(b,c)) a.(b.c)

- .(a,.(b,.(c,))) a.(b.(c.))

76

- A Second Definition of a list

- A list is either the atom , representing

the empty list, or a compound term with functor

'.' and two arguments which are respectively the

head and tail of a list. - It is an ordered sequence of elements.

- Strings

- Strings are implemented as lists of ASCII

integers, e.g. - systems 115,121,115,116,101,109,115

77

Trees

- A structure naturally corresponds to a tree or

sub-tree - tutors210(ruth, john, mike).

- may be thought of as the following tree

- tutors210 root

functor -

branches

components - ruth john mike

- Using a tree structure to show the syntax of an

English sentence - sentence (noun, verb_phrase (verb, noun))

- sentence

- noun

verb_phrase - (Jim)

78

Lists as Trees

- Lists are special kinds of trees.

- a .a,) .

- a

- a,b,c .(a,.b,c) .

- a

b,c - .(a,.(b,c)) .

- a

. -

- b c

- .(a,.(b,.(c,)))

. -

-

a .

79

Examples of Using Lists

- ?- user. 3 arguments 4

arguments - p(1,2,3).

- p(the,cat, sat,on,the,mat).

- Z

- ?- p(XY).

- X 1,

- Y 2,3

- X the,

- Y cat,sat,on,the,mat

- Yes

- ?-p(_ ,_ ,_ ,_X).

- X the,mat

- Yes

80

List Processing

- Lists can be processed in much the same way as in

Lisp (i.e. with recursive definitions). - But note the difference between a

functional definition and a relational

definition. - a functional definition

- specifies the output (result) in terms of the

input (arguments) - a relational definition

- specifies the relationship between a number of

objects (the arguments) - which terms are input and output is determined by

use - e.g. member(a,a,b,c).----------gt Yes

member(a, X). ----------gt ???

member(Y, X). -----------gt ??? - It is easy to see that the first query is

meaningful but the latter 2 are not.

81

Examples of List Relations

- Consider, for example, member and append

- / X is an element in the list /

- member(X,X_). --------------------- 1

- member(X,_Y) - member(X,Y).------ 2

- If the following query is presented

- member(d,a,b,c,d,e).

- the recursive calls are as follows

- 1. Fail

- 2. Success - member(d,a,b,c,d,e).

- 2. Success - member(d, b,c,d,e).

- 1. Fail

- 2. Success - member(d, c,d,e).

- 1. Fail

- 2. Success - member(d, d,e).

- 1. Success !!!

82

Some More List Relations

- / 3rd argument is 2nd appended to 1st.

- Bratko calls this conc .

/ - append(,L,L).

- append(XL1,L2,XL3) - append(L1,L2,L3).

- last element of a list /

- last(X,X).

- last(X,_Y) - last(X,Y).

- / two consecutive elements in a list /

- nextto(X,Y,X,Y_).

- nextto(X,Y,_Z) - nextto(X,Y,Z).

- / redefinitions using append /

- last(El,List) - append(_,El,List).

- nextto(El1,El2,List) - append(_,El1,El2_,Li

st). - member(El,List) - append(_,El_,List).

X L1 L2

X L3

83

- / two lists which are the reverse of each

other - version 1

- e.g. rev(a, b, c,X). gives X c, b,

a / - rev(,).

- rev(X,X).

- rev(HT,L) - rev(T,Z), append(Z,H,L).

- / version 2

- iterative solution - uses auxiliary relation

and accumulating argument / - / second arg to revzap is an accumulator /

- rev2(L1,L2) - revzap(L1,,L2).

- revzap(XL,L2,L3) - revzap(L,XL2,L3).

- revzap(,L,L).

- / the first list is a prefix of the second

list/ - prefix(,_).

- prefix(XL,XM) - prefix(L,M).

84

Operator Notation

- The form of all structures is prefix form, e.g.

- (X, Y)

- However, a number of operations are provided in

infix form for convenience, e.g. - X Y.

- Equals X Y

- (a) if X and Y are both uninstantiated, it

means that they will share a value when either

variable is instantiated (and then will succeed). - (b) X Y will succeed if X and Y are

instantiated and have the same value. - (c) X Y will fail if X and Y are

instantiated and if X has a different value from

Y. - (d) X Y in the case that Y is instantiated

and X is not will succeed and X is assigned the

value of Y. The reverse of this fails. - Note X Y will not cause evaluation of Y if Y

is an arithmetic expression, e g. - the sub-goal X Y 1

- will result in the instantiation of

- (Y,1) to

X

85

Other Operators

- not Operator

- not(X Y) will succeed when X Y fails.

- We would use 'not equals' or ltgt to correct our

sister-of example to eliminate self-sistering. - sister-of( X, Y ) - female(X), parents(X, M,

F),

parents(Y M, F), not( X Y ). - Note, with some versions of Prolog,

- not(X Y) is written as /(X Y)

- Other Relational Operators

- All the usual ones lt, lt, , gt, gt, ltgt

86

Properties of Prolog Operators

- Functors may be written as operators for ease of

reading. - (x,(y,z)). vs xyz

- Operators have 3 properties

- (1) position

- prefix -x

- infix ab

- postfix x!

- (2) precedence

- Each operator has a 'precedence class', i.e. an

integer in the range 1 .. max. The lower the

number, the higher is the precedence! - (3) associativity

- left associative

- right associative

(i) (ii)

87

Associativity Continued

- What does 8/2/2 mean? and 234 ??

- (8/2)/2 2 or

- 8/(2/2) 8 ??

- Definition 'A left associative operator must

have the same or lower precedence operations on

the left and lower precedence operations on the

right.' - Thus, 8 / (2 / 2) is ruled out because operator

(i) requires its second operand to have an

operator which is strictly lower in precedence - (ii) is not strictly lower than (i).

- Thus (8/2)/2 is the correct interpretation.

88

Declaring Operators

- To declare operators, you supply a 'picture' of

the operator use which defines its properties. - For infix operators, these are

- xfx, xfy, yfx, yfy

-

left associative -

right associative - For prefix operators

- fx, fy

- For postfix

- xf, yf

- Associativity

- 'y' --gt the argument can contain operators of

the same or lower precedence than this operator - 'x' --gt the argument must contain operators of

strictly lower precedence than this operator - Thus yfx is left associative

89

- Examples of built-in operator declarations

- op(31, yfx, -). left associative

- op(31, yfx, ).

- op(21, yfx, /).

- op(21, yfx, ).

- op(60, fx,not).

- op(253, fx,',').

- op(255, fx,'?').

90

User-defined Operator Definitions

- User-defined operators may be defined in the same

way - op(800,