Altruistic Punishment and Human Cooperation PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 49

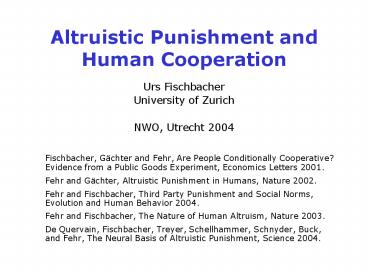

Title: Altruistic Punishment and Human Cooperation

1

Altruistic Punishment and Human Cooperation

- Urs Fischbacher

- University of Zurich

- NWO, Utrecht 2004

- Fischbacher, Gächter and Fehr, Are People

Conditionally Cooperative? Evidence from a Public

Goods Experiment, Economics Letters 2001. - Fehr and Gächter, Altruistic Punishment in

Humans, Nature 2002. - Fehr and Fischbacher, Third Party Punishment and

Social Norms, Evolution and Human Behavior 2004. - Fehr and Fischbacher, The Nature of Human

Altruism, Nature 2003. - De Quervain, Fischbacher, Treyer, Schellhammer,

Schnyder, Buck, and Fehr, The Neural Basis of

Altruistic Punishment, Science 2004.

2

Overview

- Human cooperation and strong reciprocity

- Experimental evidence for strong reciprocity

- Proximate models of strong reciprocity

- Altruistic punishment activates reward related

areas in the brain - Ultimate models of strong reciprocity

3

Humans Large-Scale Cooperation

- Humans societies are a huge anomaly in the animal

world. They are based on a detailed division of

labor and cooperation of genetically unrelated

individuals in large groups. - In most animal species there is little division

of labor and cooperation is limited to small

groups.

4

Why do Humans cooperate?

- Strategic cooperation (cooperation to induce

cooperation by the other players) in the form of - Reciprocal altruism, i.e. self-interested

exchanges in repeated interactions, at a scale

and in domains of behavior that is unprecedented

in the animal world. - Reputation-based cooperation is also a powerful

force among humans and differs in scale and in

kind from what has so far been observed in

animals. - However, human altruism even goes beyond

reciprocal altruism and reputation-based

cooperation, taking the form of strong

reciprocity.

5

Strong Reciprocity

- Is a combination of altruistic rewarding (strong

positive reciprocity) and altruistic punishment

(strong negative reciprocity). - Altruistic rewarding A readiness to incur costs

to reward others for cooperative, norm-abiding

behaviors in the absence of any individual

economic benefit for the rewarding individual. - Altruistic punishment A readiness to incur costs

to punish others for norm violations in the

absence of any individual economic benefits for

the punishing individual.

6

Public-Goods Experiment

- N players get an endowment.

- Decide simultaneously how many point of they

contribute to the public goods. - The contributions are summed up, multiplied with

a factor F (e.g. 2) and distributed equally

between all players. - If Fgt1, it is efficient to contribute

(cooperate). - If F/Nlt1, it is a dominant strategy not to

contribute (defect). - Structure mimics the logic of many important real

world examples. Whenever individual actions have

positive or negative effects on other individuals

a similar situation arises Pollution problems,

over-fishing the seas, cooperative production and

food-sharing in small-scale societies,

cooperative hunting and warfare, etc.

7

Altruistic Rewarding

- (Fischbacher et al. 2001, see also FKR 93 or BDM

95) - Standard public goods situation (endowment 20, N

4, F1.6) played only once - Subjects can make a conditional contribution to

the project, i.e. they fill out a contribution

table in which they can condition their

contribution on every possible contribution of

the others

8

Predictions

- Selfish subjects (e.g. subjects who cooperate for

strategic reasons only) always put in zero into

the schedule. - Strongly reciprocal subjects contribution

increases in the average contribution of the

other group members. - The other subjects contribution is a cooperative

act which deserves altruistic rewarding.

9

Average schedulesFischbacher, Gächter, Fehr 2001

20

18

Strong reciprocators 50

16

14

12

Own contribution

10

Mean (N44)

8

6

4

Hump-shaped 14

2

Selfish 30

0

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

20

Average contribution level of other group members

10

Altruistic Punishment (Fehr Gächter, American

Economic Review 2000, Nature 2002)

- Public goods game as above.

- Six periods to allow for learning and to study

the stability of cooperation. At the end of each

period group members are informed about

individual contributions of other group members

without revealing their identities. - No repeated interaction with the same subjects.

In each period each subject faces new group

members. - Nobody knows the previous actions of the other

group members.

11

Altruistic Punishment Treatments

- Control treatment exactly as described above.

- Punishment treatment adds the opportunity to

punish other group members after being informed

about their investments. Two Stages in each

period - The first stage is identical to the control

treatment. - At the second stage each group member can

allocate punishment points to the other members. - The first stage payoff of the punished

individuals is reduced. - Punishing is costly for the punisher. Each

"invested" into punishment reduces the payoff of

the sanctioned player by 3.

12

Predictions with selfish individuals

- Since punishment is costly for the punisher and

yields not material benefits no selfish subject

will ever punish. - If nobody punishes in the punishment condition

then the cooperation behavior in the punishment

condition is predicted to be identical to the

behavior in the control condition. - ?In both treatments cooperation should be zero.

13

Cooperation without and with punishmentSource

FehrGächter Nature 2002

without punishment

20

18

16

14

12

Mean contribution

10

8

6

4

2

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

Period

14

Cooperation without and with punishmentSource

FehrGächter Nature 2002

with punishment

without punishment

20

18

16

14

12

Mean contribution

10

8

6

4

2

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

Period

15

Cooperation with and without punishment Source

FehrGächter Nature 2002

16

Punishment

17

Is Punishment an altruistic act?

- The presence of punishers establishes a credible

threat that deters non-cooperation - all group

members benefit from this threat. - Punished subjects contribute more in the next

periods - future interaction partners of the

punished subjects benefit from the punishment. - Punishing subjects bear costs.

18

Strong reciprocity is documented in dozen of

studies

- It has been documented in a wide variety of

situations - It applies among strangers. Virtually all

experiments implement anonymous interactions

among subjects. - Confirmed under experimenter-subject anonymity

(Berg et al. 1995, Bolton and Zwick 1995, Abbink

et al. 1997, etc.) - Confirmed under rather high stake levels (Cameron

1999, Fehr, Tougareva Fischbacher 2002, three

months' income) - Confirmed under one-shot repetitions (Roth et al.

1991, Fehr et. al 1998, Charness 1996, etc.) - Strong variation across different small-scale

societies (Henrich, Boyd, Bowles, Camerer,

Gintis, Fehr McElreath 2001)

19

Proximate Motives behind Strong Reciprocity

- Inequity aversion

- Fehr Schmidt 1999, Bolton Ockenfels 2000.

- Ui pi ai pi pj

- Intention based reciprocity

- Rabin 1993, Levine 1998, Dufwenberg

Kirchsteiger 2004, Falk Fischbacher

forthcoming. - Ui pi ri kindnessj-gti pj

- All theories assume a fairness motive in addition

to self interest.

20

Neural Basis of Altruistic punishment De

Quervain, Fischbacher, ....., and Fehr, Science

2004

- There is well documented evidence for reward

related areas in the brain (Nucleus Accumbens,

Nucleus Caudate). These areas are activated when

subjects get reward in the form of - Money

- Beautiful faces

- Cocain

- Fairness theories assume that people derive

utility from altruistic rewarding and from

altruistic punishment. - Are reward related areas in the brain also

activated when subjects have the opportunity to

punish?

21

The basic game

- Two traders, A and B, are matched anonymously.

The good possessed by A is four times more worth

for trader B. Thus, if A gives the good to B and

B pays A a fair share of the gains from trade

both traders can benefit. - However, trade takes place sequentially, i.e., A

first has to give the good to B, then B pays A.

Thus, A has to trust B and B can abuse A's trust

by not paying. - Both are endowed with 10 MUs. A can send his 10

MUs to B. The experimenter quadruples this amount

so that B has, in total, 50 MUs. Then B can send

back 25 MUs to A. - After B has made his payment decision A has the

opportunity to punish B. By spending 1 MU on

punishment he can reduce B's income by 2 MUs. A

can spend up to 20 MUs on punishment.

22

Behavioral Results

- The vast majority of A sends the 10 MUs.

- Roughly 50-60 of the B's send back nothing.

- Roughly 80 of the A's punish those B's who abuse

their trust. - Average payoff reduction for the B's is 23 MUs.

23

Treatment conditions

- Punishment is costly for both A and B (Costly,

IC). A is hypothesized to experience a desire to

punish cheating and he can in fact punish. - Punishment is only symbolic, i.e., A and B have

no costs of punishing (Symbolic IS). A is also

hypothesized to experience a desire to punish

cheating but he cannot punish. - Punishment is free for A but costly for B (Free,

IF). A is hypothesized to experience a desire to

punish cheating and he can in fact punish - even

without a cost. - We scanned the brain of player A (with PET) in

the sequential trading game when A's trust was

abused and A decided whether (and how much) to

punish B.

24

Hypothesis

- The possibility for punishing unfair behavior

activates reward-related neural circuits.

(Nucleus Accumbens, Nucleus Caudate). - IF - IS is hypothesized to activate reward

related brain regions. - IC - IS is also hypothesized to activate reward

related brain regions

25

IF-IS and IC-IS do activate the caudate nucleus

26

Individuals with higher caudate activation punish

more I

- Is the activation caused by the punishment act?

27

Individuals with higher caudate activation punish

more II

- Those with high caudate activation in IF

treatment punished more in the IC treatment. - Caudate activation has to do with expected

satisfaction of punishment.

28

Overview

- Human cooperation and strong reciprocity

- Experimental evidence for strong reciprocity

- Proximate models of strong reciprocity

- Altruistic punishment activates reward related

areas in the brain - Ultimate models of strong reciprocity

29

Prevailing Evolutionary Theories of Human

Cooperation

- Kin Selection (Hamilton 1964) - Individuals are

genetically related - Reciprocal Altruism (Trivers 1971, Axelrod and

Hamilton 1981) - Individuals are engaged in

repeated interactions. Helping today yields

benefits from the other individual in the future.

- Indirect Reciprocity (Alexander 1987, Nowak and

Sigmund 1998) - Helping creates a good reputation

in the group. Individuals with a good reputation

are more likely to receive help from others in

the future. - Signaling (Zahavi and Zahavi 1997) - Cooperative

acts signal personal qualities that are not

directly observable like, e.g., good genes. The

signals generate some benefits in the future.

30

Problem of the Theories in Explaining Large-Scale

Cooperation

- Kin selection Cooperation limited to close kin.

Subjects in experiments are unrelated strangers. - Reciprocal altruism, indirect reciprocity

Cooperation limited to situation in which

reputation can be formed, cooperation in

experiments also in one-shot situations. - Signaling theory In the absence of selection

between groups it is hard to understand why the

signal is pro-social. - Moreover, all these theories apply, in principal,

equally well to many animal species. They do not

answer the question, why humans are such an

outlier.

31

Maladaption

- Theories above can rationalize strong reciprocity

only as a maladaptive trait. - i.e., the proximate mechanisms driving human

behavior are not yet fine-tuned to interactions

among unrelated people in non-repeated

interactions where reputational gains are small

or absent. - Problem of the maladaption hypothesis

- Humans are capable to distinguish between

situations in which reputation can be gained and

situation in which this is impossible.

32

Ultimatum game(Güth et al. 1982)

- A proposer and a responder are matched

anonymously. The proposer receives 10 money units

and must make one proposal how to allocate the

money between the two players. - If the responder accepts, the proposal is

implemented. If he rejects, both get nothing.

33

Ultimatum game with reputation

- Treatment condition without reputation

- Normal ultimatum game. Repeated with different

players. - Treatment condition with reputation

- Proposers get to know which offers were rejected

in the past by the responder they are matched

with. Repeated with different players. - Maladaption prediction Subject cannot

distinguish between situations in which they can

build up reputation and situation in which they

cannot. Therefore Whether responders can build

up reputation for being tough or not, they have

the same threshold for accepting.

34

Average Rejection Threshold in Ultimatum Game

with and without Reputation Formation(Source

Fehr and Fischbacher, NATURE 2003)

35

Rejection Threshold in Ultimatum Game with and

without Reputation Formation(Source Fehr and

Fischbacher, NATURE 2003)

5

4.5

4

3.5

3

Threshold with reputation

2.5

2

1.5

1

0.5

0

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

4

4.5

5

Threshold without reputation

36

Rejection Threshold in Ultimatum Game with and

without Reputation Formation(Source Fehr and

Fischbacher, NATURE 2003)

5

4.5

4

3.5

3

Threshold with reputation

2.5

2

1.5

1

0.5

0

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

4

4.5

5

Threshold without reputation

37

The Evolution of Altruistic PunishmentBoyd,

Bowles, Gintis and Richersen, PNAS 2003

- Types of behavior

- Contributors incur cost c to produce total

benefit b, which is shared equally among n group

members. - Defectors incur no costs and produce no

benefits. - Altruistic Punishers contribute and punish all

those who defect at cost k for themselves and

cost p for each defector. - If there are no punishers, individual selection

favors defectors over contributors. - If punishers are frequent, defectors do worse

than altruistic punishers and contributors. - However, contributors do always better than

altruistic punishers.

38

The Evolution of Altruistic Punishment IIBoyd,

Bowles, Gintis and Richersen, PNAS 2003

- Evolutionary dynamics

- Individual selection Individuals imitate more

successful individuals within the group. - Migration between groups.

- Group selection mechanism With some probability

unsuccessful groups are extinct and replaced by

successful groups.

39

Simulation Results Fehr/Fischbacher, Nature

2003 based on Boyd et al. PNAS 2003

1

0.9

0.8

0.7

0.6

Average cooperation rate

0.5

0.4

0.3

no punishment possible

0.2

0.1

0

2

4

8

16

32

64

128

256

Group size

40

Simulation Results Fehr/Fischbacher, Nature

2003 based on Boyd et al. PNAS 2003

1

0.9

0.8

0.7

0.6

Average cooperation rate

0.5

0.4

punishment of defectors

0.3

possible

no punishment possible

0.2

0.1

0

2

4

8

16

32

64

128

256

Group size

41

Why Does Selection not Remove Altruistic

Punishers?

- If punishers are frequent and defectors are rare,

punishers rarely incur the cost of punishment.

Thus, in the absence of mutant defectors

punishers would do equally well as pure

contributors. - In the presence of mutant defectors punishers

have a small disadvantage relative to pure

contributors. - Selection among groups can outweigh this

disadvantage of altruistic punishers. - Remark Group selection without punishment does

not work Without punishment cooperators have a

fitness disadvantage independent of their

frequency.

42

Simulation Results Fehr/Fischbacher, Nature

2003 based on Boyd et al. PNAS 2003

43

Why does Migration not Undermine Group Selection?

- Because it is based on a cultural process of

payoff-biased imitation. Those who have a high

payoff are imitated. - Traditionally, in genetic models of group

selection migration and within-group selection

remove between-group differences in the share of

defectors. Thus, group selection cannot become

operative. - Payoff-biased imitation maintains group

differences. In groups with a low share of

altruistic punishers defectors do best and they

are imitated. In groups with a high share of

punishers, contributors do best and they are

imitated and defectors do worst.

44

Summary

- Human cooperation represents a spectacular

outlier in the animal world. This is probably due

to human forms of altruism that are unique in

kind and in scope. - Reciprocal altruism and reputation-seeking are

powerful forces of cooperation in dyadic

interactions. - However, humans exhibit even strong reciprocity,

a combination of altruistic rewarding and

altruistic punishment that is associated with net

costs for the altruist. - Altruistic punishment is key for understanding

cooperation in multi-lateral interactions.

Without altruistic punishment cooperation

unravels if opportunities for altruistic

punishment exist cooperation flourishes. - Humans seem to experience altruistic punishment

as psychologically rewarding. Caudate nucleus is

a key component in the neural circuits involved

in altruistic punishment. - Reciprocal altruism and reputation-seeking are

powerful forces of cooperation in dyadic

interactions but they have difficulties in

explaining the evolution of cooperation in

N-person public goods situations.

45

The end

46

Conditional cooperation design

- (Fischbacher et al. 2001, see also FKR 93 or BDM

95) - Standard public goods situation (endowment 20, N

4, F1.6) played only once - Subjects have to make two decisions

- An unconditional contribution to the project

- A conditional contribution to the project

(conditional on every possible contribution of

the others called contribution table) - For 3 subjects, their unconditional contribution

is relevant. For a randomly selected group member

his/her contribution schedule is relevant for the

decision.

47

Testing Evolutionary Models

Environment Game(s)

Types of behavior

- Are the types complete?

- Are there no type who can invade the population?

- Does the type distribution correspond the

distribution which is actually observed? - This question can be addressed with experiments.

- Is the environment representative?

- Does the game correspond the the interaction how

it actually took place in the relevant time

period?

Evolutionary Dynamics

48

Simulation Results Fehr/Fischbacher, Nature

2003 based on Boyd et al. PNAS 2003

49

Typical experimental outcome Isaac, Walker,

Thomas (1984)

- There is cooperation.

- Cooperation declines over time.

10HN10, F7.5 4H N4, F3 10L N10, F3 4L

N4, F1.2